“In August of 2012, I met Kirk Sauer when he was hired to be the woodworking and fine arts teacher at a school where I was the vice-principal. One of my portfolios involved the support and evaluation of new teachers; Kirk was one such teacher. Six of us began meeting in late September to outline the evaluation process, to share stories of our experiences and to provide support. A second work portfolio that brought Kirk and me in contact was my responsibility as the school-wide report reader. Three times a year I read 400 progress reports in efforts to ensure they fell within the parameters of spelling, sentence structure, word choice and content. Meeting with Kirk, observing him teach lessons and reading his report cards, I had questions. Because of my background as an Orton-Gillingham trained tutor, I began to wonder if Kirk was dyslexic. I thought about how to approach the conversation; I wanted to be professional and invitational. I decided it best to be straightforward. Kirk was not a young man.

In the many conversations we had, I understood him to be bright, articulate, and thoughtful. I sent him an email inviting him to a meeting. We began speaking and within a few moments it was clear to me he had never been diagnosed as a dyslexic nor did he understand the term. He willingly shared experiences from his childhood about learning to read and write. The more he shared, the more I thought he fit the profile. I shared what I was thinking and suspected; I asked if he would be willing to be tested. He agreed. Within a week, we completed the testing; Kirk is dyslexic. He is also a painter. His work has been exhibited locally, provincially and nationally. He lives in Dundas, Ontario.”

Sandra:

“Do you feel that most people understand what it means to be dyslexic?”

Kirk:

“My experience is that few understand. I do not feel dyslexia is given the credibility of being a major learning difficulty. This is strange because many people are dyslexic. I think the educational system is afraid to say the word and more afraid to recognize the children who are dyslexic.”

“I don’t understand why the boards of education are afraid. What would it mean to a school if kids were diagnosed with dyslexia? Do they fear it will become a legal matter that might end up costing them millions? Maybe they are afraid because once school boards accept dyslexia and diagnose children with it then the entire system will have to adjust to accommodate the kids. I don’t think schools are prepared to adjust.”

Sandra:

“Did your teachers understand your difficulties?”

Kirk:

“The teachers at my school did not understand my difficulties. There was no information available for teachers. I was called lazy, stupid, a ditch digger. Every possible negative word, phrase and sentence was used to describe me. I became belligerent. We had spelling bees every week. The teacher would assign me to a team and expect me to get up and join in. Once the teams were selected, I was given a word to spell. I did not answer and simply went and sat at my desk, even if I could spell the word. I knew that at some point the teacher would give me a word I could not spell and he would then ridicule me in front of the class. I refused to give him that satisfaction.”

“The teacher would summon the principal. The principal would arrive and I received a strapping. I did it to get the kids laughing and to hide my fear of not being able to read and correctly spell. I treated the spelling bees as a joke knowing the teachers’ strappings were never anything like the strappings from my father. It was a different world of hurt when my dad strapped me.”

“School was not that important. In the spring and late fall, I went to the river, I skipped school. My mother always knew. After moving to London, Ontario I was truly confused because of my second try at grade 9; I barely scraped through! At the same time, I became the school chess champion and beat all the geeks. Yet I could not read.”

Sandra:

“How did you understand your school life?”

Kirk:

“I felt I was as smart as any kid in my class. I could hunt, fish, draw and I played all kinds of sports. I lived next to the reserve and I spent lots of time with Native friends. I understood plants from the point of view of drawing them. I could see and was interested in things other kids could not see. I would try to explain how the light was influencing what I saw so they could also see it. I tried to teach them to see what I saw and then draw it.”

“I had an interest in and an understanding of many things. At home, I had household responsibilities early and I was expected to do the work assigned to me. I grew up in a relatively poor household and my Dad was an alcoholic. My mother was a fierce protector of me. She was a very hard worker, and I suspect she too was dyslexic. She left school early to provide for younger siblings.”

Sandra

“Do you wish you were not dyslexic?”

Kirk:

“No! I wish my elementary teachers could have explained to me that I am dyslexic. If they had an understanding of dyslexia and if they had shared it with me, I would have been much more focused on school and being academically successful. It took me nine years to complete high school. I was a gifted athlete. I set the Canadian junior record for pole vaulting when I was 15 years old. One of the coaches from Western University approached me and talked to me about an athletic scholarship for pole vaulting. I told him we did not have money for university. He said I did not need to worry about finances; the university would cover the costs. I thought about it and told him I would get back to him.”

“I never did. I quit sports at 15 because I knew I would never be successful at university; I was failing high school. Today I know that had I understood my dyslexia, I would have taken steps to be a better reader and student and I would have accepted the scholarship. I did not understand what my problem was so I did not know what to do about it. My mother believed in me. Every July I attended summer school as well as tutoring that my mother arranged for me.”

Sandra:

“Can you describe the process of learning you are dyslexic?”

Kirk:

“When we were working at the same school, you asked me many questions. One day you asked about dyslexia. I knew the word but I never thought of myself as dyslexic; I knew very little about dyslexia. I was 68 when you told me. My world shattered. I had to reassess everything. I spent time wondering. My dyslexia taught me to be constantly evaluating. I decided to avoid the pity party and chose vindication instead. You kept checking on me and we continued to talk.”

“I realized that after all these years, I finally understood a great deal more about myself. It did not matter which lens I looked through, or which problem I evaluated, it all made sense. So many of my struggles were largely a reflection of my dyslexia. I realized who I was and I knew there were no more barriers; I felt reborn. Before I learned I was dyslexic, I had a good life but I always felt I was living while looking through a window. Sometimes the window was clear and at other times, it was not.”

“Once you said the word dyslexia and you explained it in detail and I read all those books you gave me, my identity shifted. I am still living a good life but now I am standing in front of a screen door and the air is moving freely and I breathe it and in so doing I see and experience so many more nuances. I know I can do anything as long as I put my mind to it.”

Sandra:

“That is stunning Kirk. I forgot how you talk as if you are narrating a movie. So many images are floating in my mind; thank you. I would now like to ask you what kind of a reader you are today.”

Kirk:

“My reading has moved into childhood interests. These are no longer barred to me. I now read music, I’m learning songs and I’m thinking about taking guitar lessons. I read various artists’ biographies and enjoy the theory side of art. I have two art degrees and a year of classical Atelier training from Florence Italy. I also read about travel as I have had the privilege of living in other countries and have visited over forty. People interest me so much and now I cannot only meet them I can also read about them.

“One new realization I have come to understand is I no longer have to make apologies for the way I speak or write. My brain is picture based and often when I speak I am suddenly caught up in the picture-making process inside my head (on the subject at hand) and I have to let it run its course, of building a completed image before I can re-engage in the conversation or complete a written sentence. I now understand why I so dislike speaking with more than one person. I simply cannot follow two people speaking at once. I go into information- picture-image overload and my brain screen turns into muddy misshapen colour images that flow downward.”

Sandra:

“What is the hardest thing about reading?”

Kirk:

“I still find my brain and my hearing are not as connected as I would like them to be; there are sounds I miss. When I look at text, I realize I said something wrong. When I use the narration feature on the computer, I see there is a difference between what the narrator says and what I see and read. The larger the number of inputs (auditory, visual and kinesthetic tactile, when I type) the better the chance of understanding and getting the word right. I read a word, sentence or phrase aloud then the computer speaks it and I hear it inside my head. I am noticing that what I say and think is not always the same as what the computer says. This is an area I continue to work on. I know we talked about this in the north and that you were supporting teachers to use a multisensory approach when planning and delivering lessons. “

“Now I know it from the side of a learner and it is very helpful and simply wonderful. Thank you for pointing me to the assistive technology. Without it, I do not think I would have taken up writing the way I have. I now use a very large screen to see what I write. This allows me to get up and walk around and still be able to read the screen while the narrator is working. The standing and walking somehow allows me to concentrate better and keeps my mind from being distracted. I learned long ago that if I have a problem and need to think it out, driving my car keeps a certain part of my brain occupied to the point where I am no longer distracted when thinking is required. This is similar to what I do now when I walk around while looking at my large computer screen and listening to the narrator; I am able to focus my attention. Large print helps when using the larger screen. As well, music scores became readable and easier to remember when enlarged.”

Sandra:

“What was your least favourite thing about learning to read?”

Kirk:

“I was strapped frequently for not being able to read and spell. My mother was brought to school regularly and the principal made fun of me indirectly. During my early elementary school days, there was a litany of questions focused on understanding why I was attending the school or why I was not in the special education class.“

“The lessons did not make sense to me. Teachers would write on the board, read aloud and then expect me to understand. I did not. This teaching method did not work for me and they did not have an alternative. It resulted in an enormous internal conflict because I knew I was smart; however, my inability to grasp demoralized me and I began to recede, I got angry and I rebelled. There was no way for me to win, it constantly reaffirmed to me how dumb I was or rather how dumb they believed me to be.”

“Sandra:

“Are you angry?”

Kirk:

“I used to be before I understood dyslexia. Now, I create paintings and I am writing. No time to be angry. I see my extra efforts put into learning are paying off. I know it has been a process in terms of accepting my dyslexia and I am grateful for those who have supported me along the way.”

Sandra:

“Why did it take us 68 years?”

Kirk:

“My child is dyslexic. He went to a special school. He repeated a grade in public school. My wife took a lawyer to the school board and it ended with our child being sent to a special school, instead of the board being sued. Nevertheless, my child’s life was changed irrevocably, he was behind his friends and was cast out of his social life. I worry because I know children continue to endure terrible things at school from teachers who don’t know how to teach them in ways that will allow them to be readers and writers.”

Sandra:

“Do you want to be a better reader?”

Kirk:

“Always, The nuances of life make reading and writing sparkle.”

“Words are becoming the reflected light bouncing off something whose shape is more defined and interesting because my reading and writing are constantly improving. I missed this in the past. That little extra is the nuance that completes ideas. When I could not read and write with full understanding, I missed the magic. I expect most of the children with dyslexia who are not being given the correct type of teaching are also missing out on life’s little bits of magic.”

“The first time the wind passed through the screen door, I inhaled new air I had never breathed before which filled me with wonder. Now that I know, I am dyslexic and I am working hard at becoming a better reader and allowing myself to engage in writing, I get to experience a different world. It is a bigger world and much more interesting, alive and inclusive”

Sandra:

“Did your mom understand?”

Kirk:

“We never talked about it. I don’t think she really understood. She started working very early. Mother helped raise her younger siblings. I expect she saw herself reflected in me. She was a positive, articulate woman.”

Sandra:

“Do you like libraries?”

Kirk:

“No. But I love art galleries”

Sandra:

“Did you like to be read aloud to?”

Kirk:

No one ever read aloud to me. My dad did not read to me. He barely spoke to me.

Sandra:

“What is the best thing about being dyslexic?”

Kirk:

“My highs are higher, my understanding is better and I tend to stay in the learning mood until I know the subject totally. My interests from childhood are now being attained. I like the fact that I now know myself and my abilities. I have worked harder at getting to know myself and appreciate the rewards. I no longer wake up in the morning with any form of dread about what is to be done today.”

Sandra

“What would you tell children living with dyslexia?”

Kirk:

“I would tell them to stay with their dreams and fantasies and hold them close as they are their future. Take the time to learn your strengths and weakness. Do not spend all your time on your weaknesses. Enjoy and exercise your strengths. The strengths are the foundations on which you will build your home and life. If the criteria for the human condition is to find people to keep us moving forward then we want the dyslexics to help with the complex issues. If I was going to build something, I would want people who can see what is needed now with built-in extras for the future. As computers become more advanced, the dyslexic of the future will have more relevance in so many jobs. We see and experience the world differently. As so much of the linear, mundane jobs are handled by computers, the mind of dyslexics will become increasingly valued because we think creatively, outside the box and we are problem solvers. This is the case because the educational system forced us to survive in a world that refused to meet our learning needs, so we innovated.”

Sandra

“Why should we use the word dyslexia?”

Kirk:

“It is a word that is recognized by society. Why not, what is the stumbling block with boards of education? What are the fears if this word is used?”

'“If we don’t have students who are dyslexic then we don’t have to have teachers to remediate it. I do not want children to experience what I did. Someone has to say we will not allow children to suffer because they don’t learn to read and write in response to current teaching pedagogies. I took 9 years to get through 4 years of high school. I want to sue the high school. We have to take on a school board and set a precedent. We need a court case. At school, if you are bright, you will be moved forward or put into a gifted class. If someone is bright and advanced we laud them. If someone has difficulties we avoid them. Teachers just repeat and repeat the “normal” way of teaching. This doesn’t work for us. They need a fresh approach that can readily be put into place, as other teaching institutions are doing. When I was teaching kids with dyslexia, I had the time of my life because I saw myself reflected in them. The kids knew I was also dyslexic. Some were better readers than I. Once they found out I was dyslexic, the kids loved it.”

“Today I am a better reader. I am a different person. It stuns me, it thrills me; I am learning about and liking this new guy. I am writing a memoir and my editor is engaging me to say more about my own experiences. So good to have it down on paper. I am a long way from home plate. It is like a painting, a layering process, transparent, semi-opaque, opaque on a canvas The best thing about tutoring a kid with dyslexia, the pieces to their puzzles are always changing. The challenge is to feel, see and hear what is going on inside them. This is exciting and fraught with promise. The challenge is to keep up.”

Sandra Jack-Malik, Ph.D.: Assistant Professor in the Department of Education at Cape Breton University in Nova Scotia. She teaches curriculum and instruction courses in English language arts to elementary and secondary preservice teachers. A qualitative researcher, her primary interests lie at the intersections of literacies and identities and the pedagogies that support students to close achievement gaps. She is also interested in the experiences of preservice and in-service teachers as they work to support struggling students and the implications these understandings can have on teacher

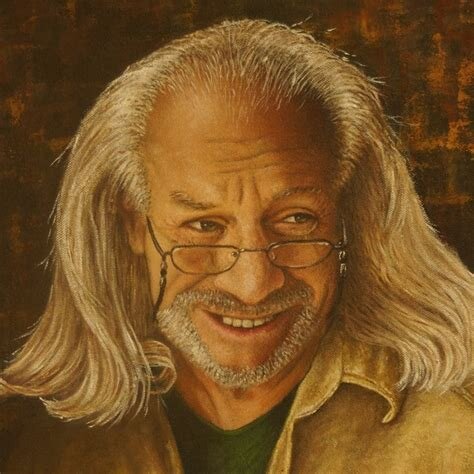

Kirk Sauer: Artist, teacher, traveller, dyslexic and visionary, Kirk Sauer is attracted by diversity. After a fine art degree and a successful sales management career in architectural woodworking, Kirk took a daring break back to the art world, attaining another art degree from OCAD University, including one year of classical training in Florence Italy. While teaching art, first at UBC, then in remote fly-in native villages, Kirk presented three successful art shows in the western provinces. The subjects centred around his depiction of his First Nations northern community experiences, and figurative works of abused men and women, wherein he explored his own abuse due to his dyslexia.